Published on 11/16/2016 | Market Sizing

There’ll be a new civilization, the sum of human intelligence and artificial intelligence, where artificial intelligence will be able to analyze a problem, identify the resources needed to deal with it, plan a strategy, adapt and improve itself to resolve the problem.” It will do this not only for specific, planned objectives – like the IBM computer that beat chess champion Garry Kasparov in 1996 or the vision system that recognizes obstacles in today’s self-driving cars – but “in a generalized way, with any problem”. This will happen soon, “within the next two or three decades”. A valuable time “for us to get ready for a world that will see huge changes, and make sure the effects are positive and compatible with people’s lives and aspirations”.

Singularity is a key concept for Orban. Specifically, “technological singularity”, the hypothetical moment in time when, with the support of increasingly powerful computers, the world will move from so-called “restricted” artificial intelligence (such as the vision system in a driverless car) to “strong” artificial intelligence (able to adapt itself to achieve generalized goals).

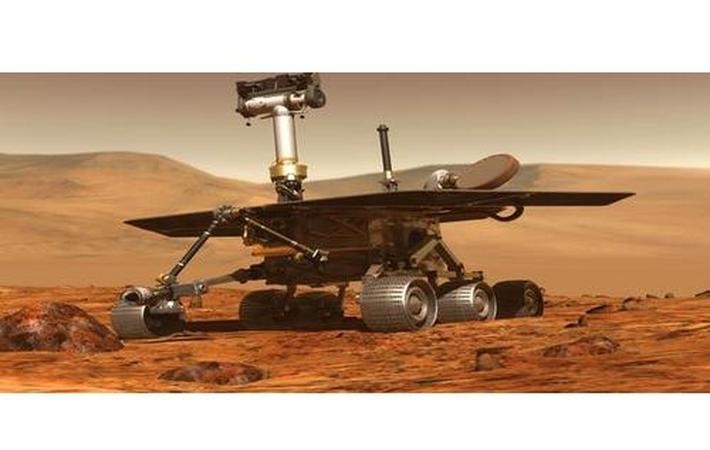

“In strong artificial intelligence, space colonization systems will play a leading role,” says Orban. “We have already conquered Mars, but we’ve never set foot on the planet, our robots have done that. The probes covering the surface of the ‘red planet’ are relatively simple at the moment, but they are already becoming more sophisticated and will become more so, able to plan their routes themselves, where to go, what experiments to perform.” They will also be more fully equipped and better able to adapt than people. “We have to drink, eat, breathe, we can’t devote all our resources to exploration. Artificial intelligence on the other hand will say ‘I don’t need human hands, or to walk in Earth’s gravity, I want to be tiny so I can be accelerated through space by a laser beam, I want to be replicated in billions of copies so that if a few dozen or a few million copies perish during the exploration there won’t be repercussions, I want to expand like a cloud to explore the solar system and beyond’.”

These operations are beyond our capabilities. And such entities are currently very difficult to imagine and visualize. “Even though the extreme anthropomorphization of artificial intelligence will be inevitable and necessary, it will be considered naïve, almost childish,” Orban predicts, “like the machines imagined by Hollywood, where robots thirst for women or power and want to conquer or destroy. The systems will be quite different to us.” So we shouldn’t imagine friendly faces that blush or arms that help us with the housework and ask us what we need. Although, Orban explains, “those are very important achievements, and help us learn to live with advanced intelligence.”

Another example of “strong” applications, he adds, could be management of cities. From energy and schools to policy and regulations, a complex system of objectives achieved by organizing resources and taking decisions. “There won’t be a Terminator who goes around exterminating people, and then turns good, but an intelligence with the ability, for example, to forecast population ageing and climate change, and find suitable solutions, and with a planning and adaptation capacity superior to that historically and statistically shown by humans.”

Orban’s positive outlook is in contrast to that of people like Elon Musk or Steve Hawking, who fear that such powerful technologies could destroy the human race. “There aren’t any guarantees, but I’m cautiously optimistic,” says Orban. “Identifying the parameters that can be managed in the evolution of the systems of the future is something we can and must do,” he adds. “The desires and goals of these systems will depend on how we incentivize and design them and on the type of moral principles they have inside them. From this point of view, the next 20-30 years will be crucial. The decisions of strong artificial intelligence will have immeasurable ethical implications. But look at what’s already happening with restricted intelligence: driverless cars stop at red lights and give way, because although they have to take the passenger to their destination, they don’t do so at any cost.”

It’s a wider question, according to Orban. “Over the centuries, people have worked to improve agriculture, architecture, engineering, but we have never developed a science of ethics. We’ve been happy with the clay tablets of the bronze age that codify our morality and Shakespeare’s sonnets, which explore its paradoxes. The Google engineers whose daily job is to encode the behavioral rules of self-driving cars have a responsibility they would not have if they could only refer to a science, in the same way that someone who is building a bridge does to make sure it doesn’t collapse.” “Our analysis of developments in artificial intelligence,” urges the professor, “should include a world-level program on the science of morality, like the ‘Apollo program’ that took us to the moon.”

This isn’t the only critical issue. “We also need to review the social contract,” says Orban in reply to those who fear that the advent of such advanced systems will lead to even greater job losses. “This is already happening with restricted artificial intelligence,” he explains. “As soon as driverless cars really achieve critical mass, the two million truckers in the US will be out of a job. The typical response is ‘Why don’t they become web designers? They’re in big demand.’ But the average US truck driver is 55, when is he or she going to build a new skill set? Today we think work is the purpose of our lives, but this isn’t a great model. We have to re-think human dignity, ask ourselves how we can be constructive members of society, apart from work. I don’t know whether a citizen’s income is the answer,” he adds, “but it could be part of a useful debate, which is not taking place at the moment.”

Society should also be more tolerant, says Orban, of people who decide to throw in the towel. According to his theory, most technological change is exponential, but “whereas in the Middle Ages, it occurred over whole generations, today it takes less time.” “It will be in our lifetimes,” he says. “That’s why guaranteeing people the right to live in a world to which they are unable to adapt is very important.” Unless we want to do what they did to the American Indians, “we didn’t recognize their rights, and killed them all.”

You can find the original article here.